The Fed’s Out of Ammo: Why the Real Crisis Is a Liquidity One

The market isn’t struggling with interest rates, it’s running out of cash, and the Fed’s running out of room to fix it.

The Real Problem Isn’t Rates, It’s Cash Flow

Everyone’s still arguing about rate cuts, but the bigger story is hiding in the background: the system is quietly running low on cash. In finance, this cash flow is called liquidity, it’s what keeps money moving between banks, funds, and investors. Think of liquidity as the oil that keeps an engine running smoothly. Without it, the gears grind, and eventually, the engine stops. Right now, that oil is draining faster than most people realize.

What “Reserves” Actually Mean

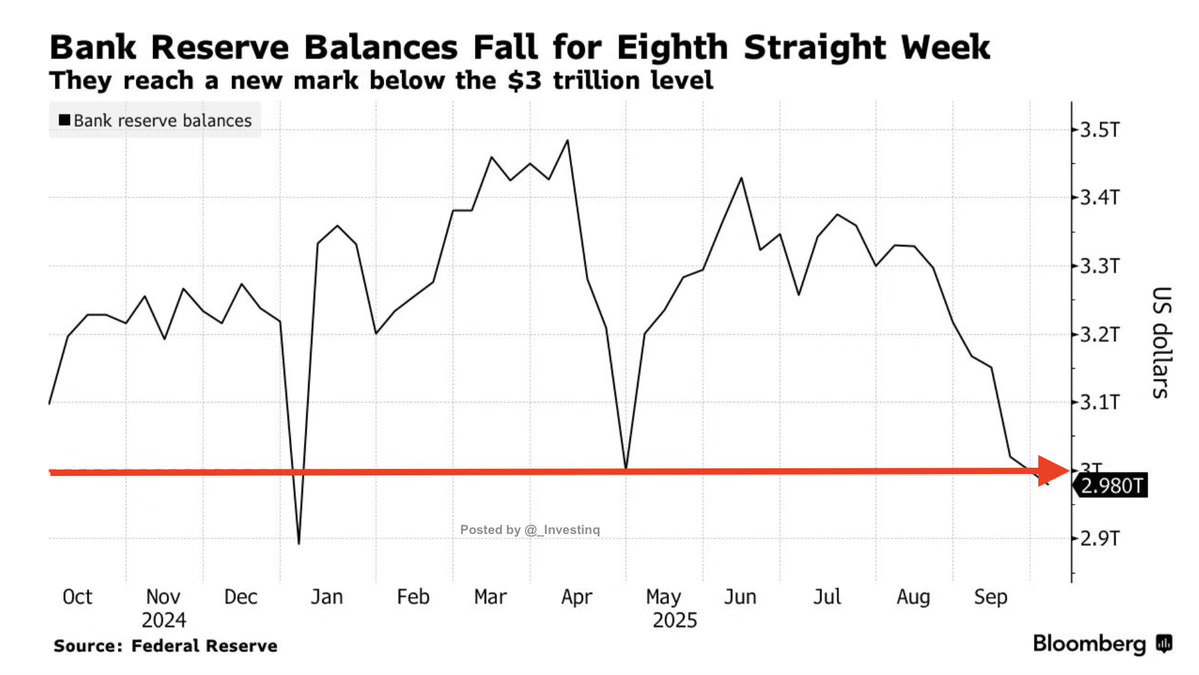

At the center of this issue are bank reserves, which are basically the savings accounts that commercial banks keep at the Federal Reserve. They use these reserves to settle payments with each other every day like Venmo for banks, but on a trillion-dollar scale. Those reserves fell below $3 trillion, a level the Fed quietly considers the border between plenty of liquidity and not enough.

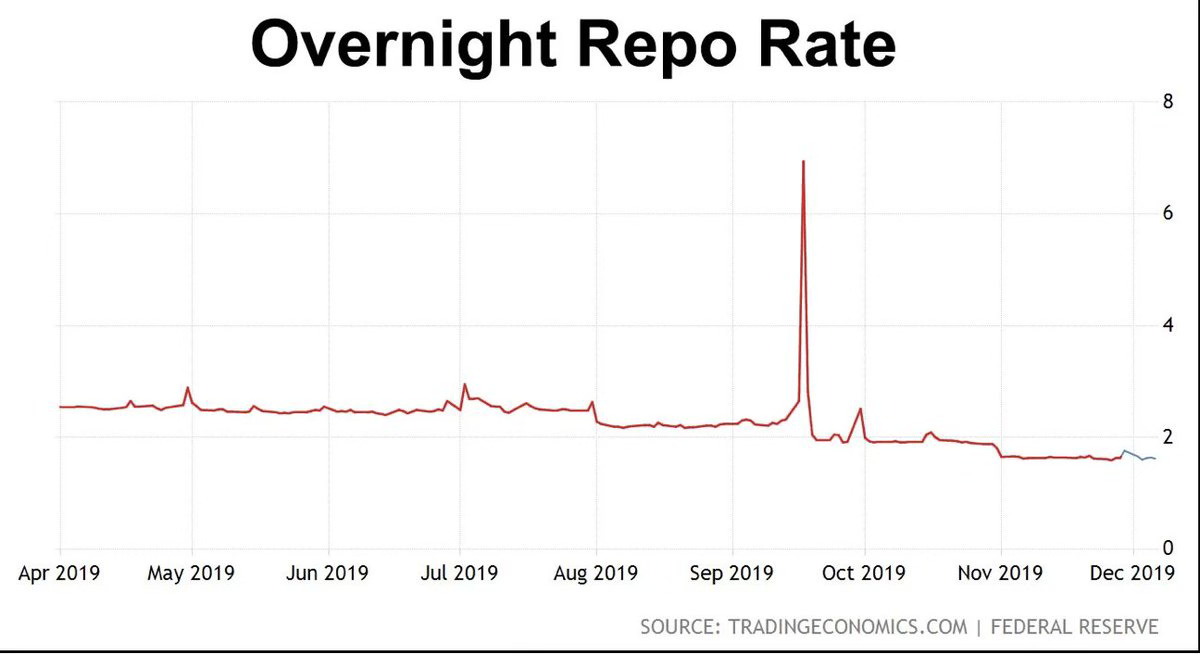

When reserves become scarce, banks get cautious. They stop lending as freely, interest rates in short-term markets start to rise, and parts of the system begin to strain. This same problem happened in 2019 when short-term borrowing rates suddenly spiked, forcing the Fed to step in with emergency cash. Back then, it took everyone by surprise. Now, the signs are starting to show again.

How the Fed Drained the Pool

This time, the shortage comes from something called quantitative tightening, or QT. During the pandemic, the Fed did the opposite, quantitative easing (QE) where it printed money and bought government bonds to keep the economy afloat. QT is like running that in reverse: instead of buying bonds, the Fed lets them mature without replacing them, slowly pulling cash out of the system.

Imagine a big swimming pool of money. QE filled it to the top; QT has been draining it for two years. Everything looks fine until the water level gets low enough that the pumps start sucking air. That’s roughly where we are now, which is why yesterday Chair Jerome Powell has hinted the Fed might stop QT soon, because draining much more could break something.

The Reverse Repo Well Is Running Dry

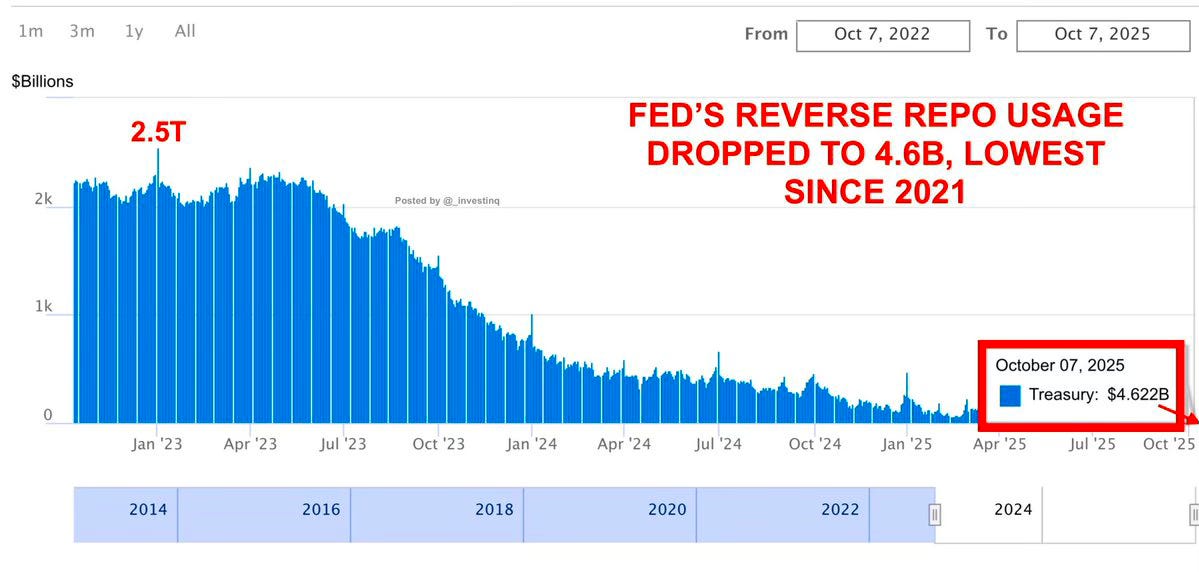

To understand how the system has stayed stable so far, you have to know about the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP). It’s like a parking lot where large institutions, think money-market funds can leave extra cash overnight and earn a tiny return. At its peak in 2022, it held about $2.5 trillion. That meant there was still plenty of spare money sloshing around.

Now that parking lot is almost empty down to just a few billion. That tells us the system’s “extra cash” has been used up. The RRP used to help fund government borrowing through short-term Treasury bills. With it drying up, the government now has to rely on regular investors to buy that debt instead. In other words, the spare tire is gone, and every mile from here on out puts more stress on the system.

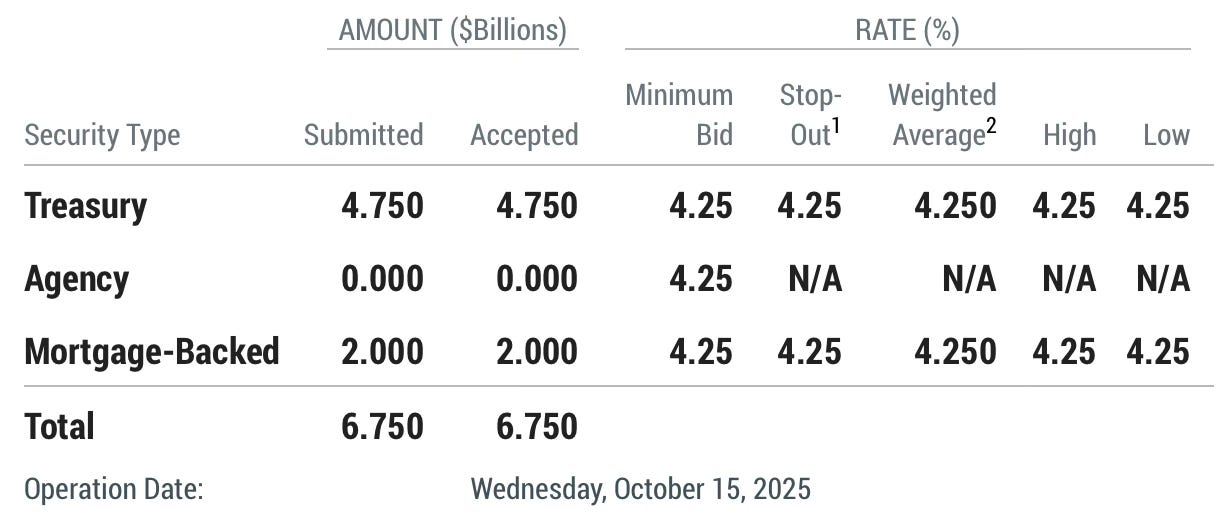

The Standing Repo Facility Starts Flashing

At the same time, the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) has suddenly come back to life. This is an emergency tool that lets banks borrow cash overnight from the Fed by using Treasuries as collateral. Think of it as the fire extinguisher on the wall, rarely touched unless something starts to smoke.

This week, banks borrowed $6.75 billion from it, the largest non-quarter-end amount since the 2020 crisis. That might not sound huge, but it’s a warning sign. Normally, the SRF sits at zero. When it jumps like this, it means banks are having trouble finding cash in the open market and are knocking on the Fed’s door instead.

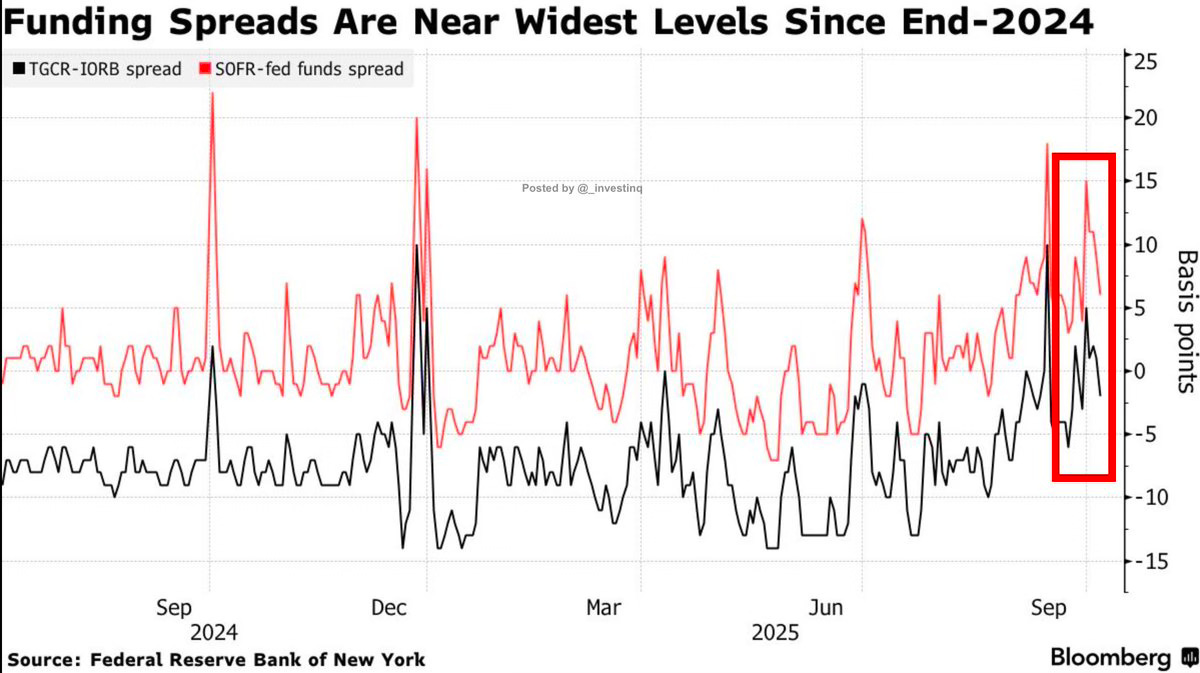

SOFR — The System’s Heartbeat

Another subtle sign comes from something called SOFR, short for the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. It’s the average interest rate that banks charge each other to borrow cash overnight using Treasuries as collateral. It’s basically the pulse of the entire funding system.

Recently, SOFR has started to trade slightly higher than the Fed’s own rate on reserves (the IORB). That might sound like small talk, but it’s the market’s way of saying, “Cash is getting harder to find.” When SOFR rises above IORB, it means the demand for cash is exceeding supply like seeing the water pressure drop before the faucet goes dry.

Why the Fed Is Cornered

Here’s the problem: the Fed can’t solve this by just cutting interest rates. Lower rates might make borrowing cheaper, but they don’t create new reserves. When there isn’t enough cash in the system, the only real fix is for the Fed to pump some back in. That could mean stopping QT early or restarting some kind of liquidity program maybe not calling it “quantitative easing,” but doing something that looks a lot like it.

What It Means for Markets

When liquidity tightens, everything in markets starts to feel heavier. Stocks can still rise for a while, but every rally takes more effort. It’s like trying to swim while the tide is quietly going out, you might not notice at first, but the current is moving against you.

The biggest impact shows up in risk appetite. Liquidity is the invisible fuel that drives investor confidence. When there’s plenty of it, people take more risks, they buy growth stocks, speculate on crypto, and pile into high-yield bonds. When liquidity shrinks, that confidence fades. Investors pull back to safer assets like cash, Treasuries, or gold. So even if earnings look fine or inflation keeps cooling, shrinking liquidity can still drag prices lower across risk assets.

Stocks tend to struggle in these environments not because of bad fundamentals, but because there’s less money available to buy them. That’s why you’ll sometimes see markets fall even when news looks good, it’s not about sentiment, it’s about flows. Large funds, passive ETFs, and systematic traders all depend on abundant liquidity to function smoothly. Once reserves start tightening, those flows weaken, and volatility creeps back in.

Bonds feel it too. When liquidity gets tight, short-term interest rates rise first as banks compete for scarce cash. That pushes up yields in funding-sensitive areas like Treasury bills, repo markets, and money markets. Longer-term yields can move either direction depending on how much stress investors expect ahead, sometimes falling as people rush to safety, other times rising if markets fear the Fed will have to restart QE and flood the system again.

And then there’s credit and leverage. Companies that rely heavily on short-term borrowing like smaller banks, REITs, or leveraged hedge funds get squeezed the fastest. Funding costs rise, access to cheap debt disappears, and weak links start to snap. This is how a quiet liquidity problem can suddenly turn into a market event.

In short: when the financial system’s “oxygen” runs low, markets start to hold their breath. It doesn’t mean an immediate crash, but it does mean the margin for error gets razor thin. Every data point, every Fed comment, every Treasury auction begins to matter more.

That’s why traders are watching the same indicators the Fed is SOFR, repo usage, and Fed reserves. If those numbers keep tightening, the market may force the Fed’s hand sooner than expected. And if the Fed does step in with liquidity injections again, it’ll mark the next big turning point, one that could reignite risk assets, but also confirm that the system just can’t stand on its own anymore.

For now, stocks may keep drifting on momentum and passive inflows but under the surface, the market is running on thinner oxygen by the day. The real story of 2025 might not be rate cuts or inflation at all, it could be how long the Fed can keep this liquidity game going before something breaks.

You brought the real culprit out in the open..I don’t think not even 5% understand the subtleties of financial shenanigans going on behind the doors…no wonder precious metals are smelling something rotten in the system

Fascinating! This is an excellent description of how so many things can be affected by one key factor. As they say: "Cash flow is king!" Very well explained.