The Hidden Risk in U.S. Banks: Unrealized Losses in Securities Portfolios

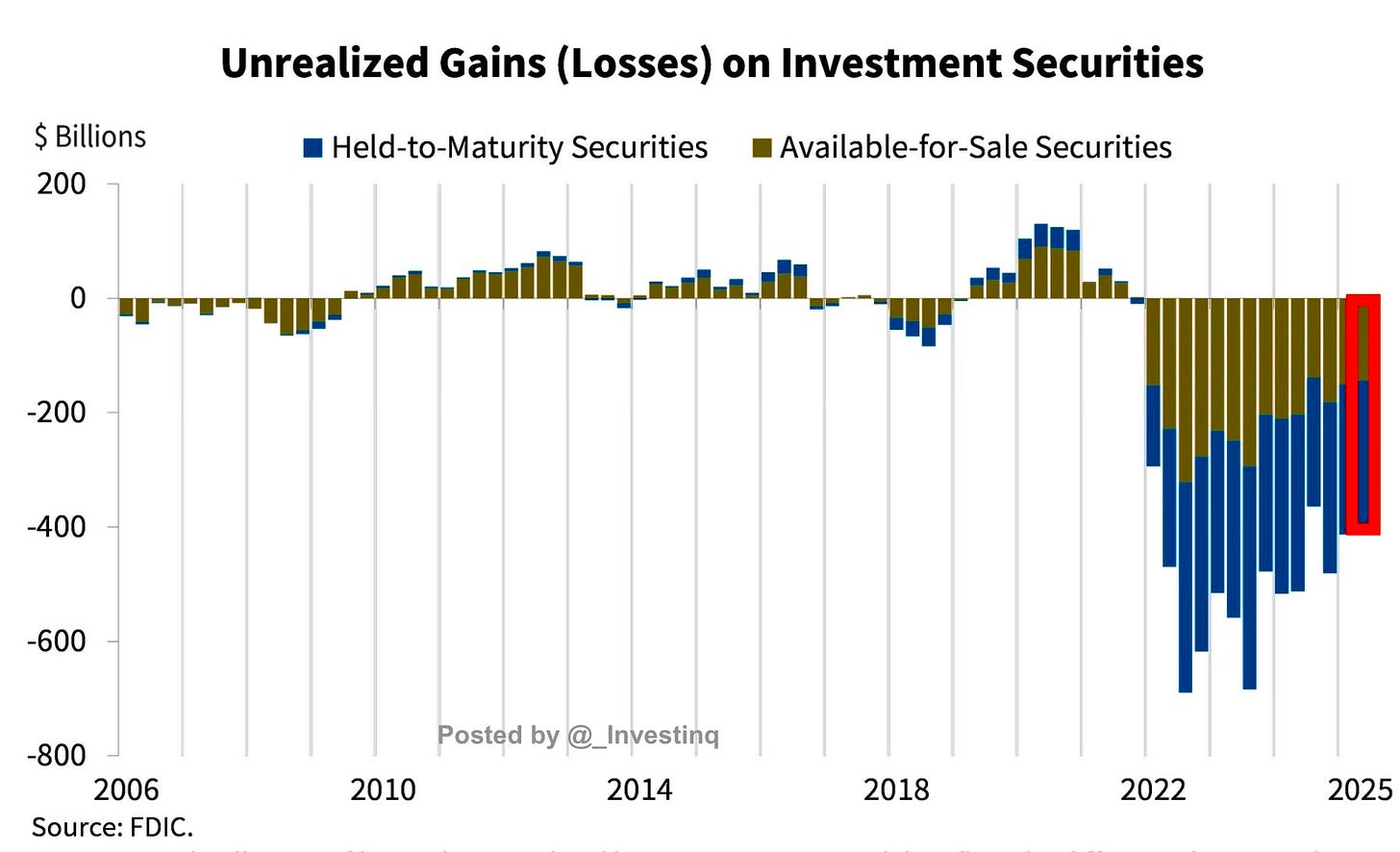

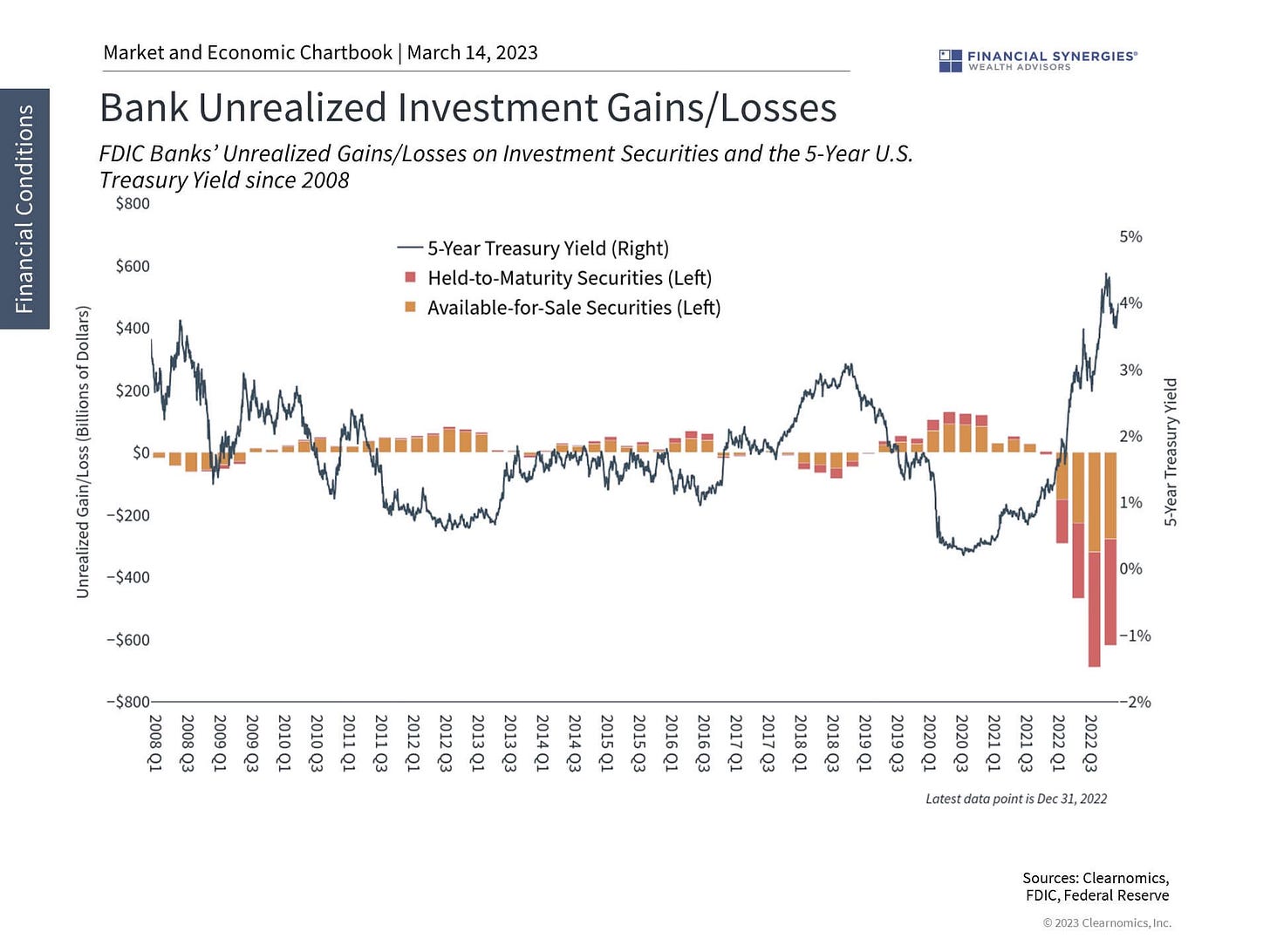

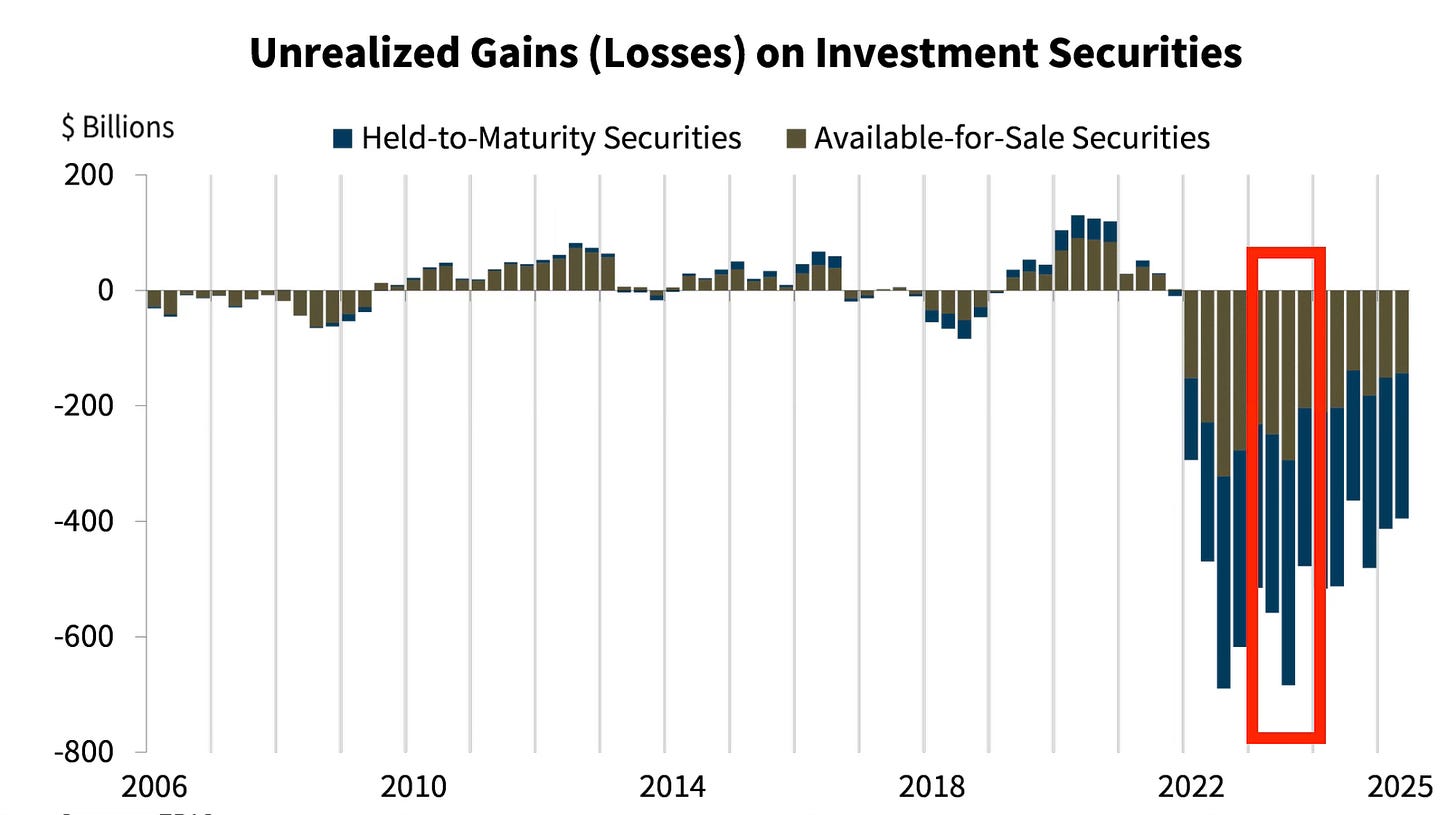

At the heart of the U.S. banking system sits a quiet but significant issue: hundreds of billions of dollars in unrealized losses on bond portfolios. These losses are not always visible in financial statements, but they weaken bank balance sheets, restrict lending, and have the potential to undermine confidence if conditions change. As of the second quarter of 2025, banks were still holding nearly four hundred billion dollars of these losses, a level that remains historically high even after some modest improvement from the peak.

What Unrealized Losses Really Mean

An unrealized loss occurs when the market value of an asset falls below the purchase price, but the asset has not yet been sold. For banks, this usually involves fixed-income securities such as U.S. Treasuries or mortgage-backed securities. A Treasury bond, for example, pays a fixed coupon. If a bank purchased that bond when interest rates were two percent and market rates later rise to five percent, the bond’s market value drops because investors can now buy new bonds with higher yields. Until the bank sells the bond, the decline in value is considered unrealized.

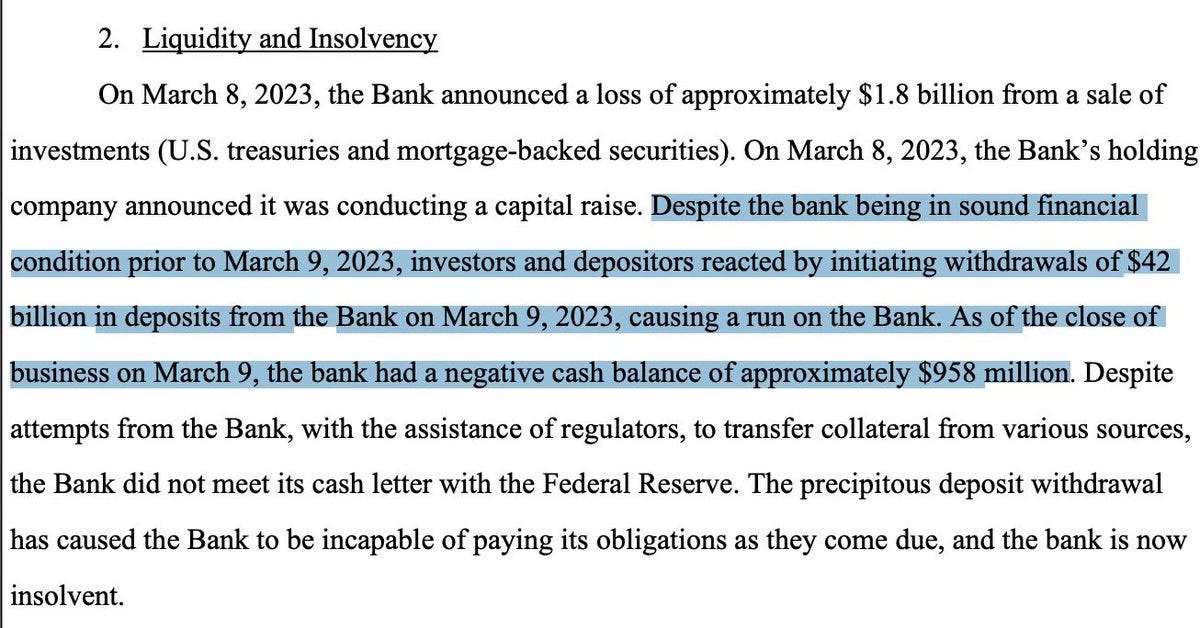

While these losses are not immediately booked on the income statement, they still matter. They reduce the true economic value of a bank’s equity, meaning the bank is not as strong as its official numbers suggest. They also create a vulnerability: if a bank suddenly needs liquidity and is forced to sell, the paper loss becomes a realized hit to capital. This is precisely what toppled several institutions in 2023 when depositors fled and banks had no choice but to sell underwater securities.

Why Banks Hold So Many Bonds

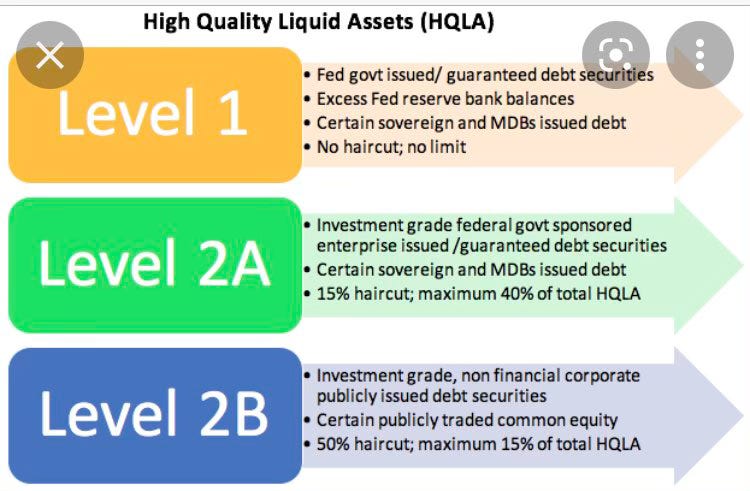

Banks maintain large bond portfolios for both regulatory and practical reasons. Regulations require them to hold high-quality liquid assets, often referred to as HQLA, which ensure they can meet sudden withdrawals. U.S. Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities qualify as the highest tier of these assets.

Beyond regulation, banks often face periods when deposits exceed loan demand. In those cases, they invest the excess funds in securities to earn interest rather than leaving the cash idle. During the pandemic years, when deposits surged and rates were near historic lows, many banks purchased long-term bonds in search of slightly higher returns. Those purchases looked safe at the time, but they locked in interest-rate risk that would later prove costly

The Scale of the Problem

The numbers illustrate just how large this issue has become. Unrealized losses peaked in late 2023 at around six hundred eighty billion dollars when long-term Treasury yields rose sharply above four and a half percent. By the end of 2024, the figure had eased to about four hundred eighty billion. In the first quarter of 2025, it stood at four hundred fourteen billion, and by the end of the second quarter losses were roughly three hundred ninety-five billion.

Even at this lower level, losses equal about one fifth of total bank equity capital. In practice, that means if every bond were marked to its current market value, banks would lose about twenty percent of their equity cushion. Most of the losses stem from mortgage-backed securities, particularly thirty-year agency bonds that were purchased when mortgage rates were three percent or lower. Treasury securities also contributed significantly, though their losses were less severe on a relative basis since many banks held shorter maturities.

Why Banks Avoid Selling

If these securities are so deeply underwater, why don’t banks sell them and move on? The answer is capital preservation. Selling at a loss would immediately reduce earnings and equity, pushing some banks dangerously close to breaching regulatory minimums. In a few cases, the losses are so large they exceed the bank’s entire common equity tier one capital, or CET1, which is the core measure of financial strength consisting of common stock and retained earnings. CET1 is the capital buffer that regulators rely on to absorb losses during stress. If it falls too low, regulators can force banks to raise capital, merge with stronger peers, or even close.

Accounting rules also discourage sales. Securities categorized as available-for-sale are marked to market through a line in equity called accumulated other comprehensive income, or AOCI. By contrast, those classified as held-to-maturity are kept at their purchase price on the balance sheet, with losses disclosed only in footnotes. Most small and mid-sized banks also opted out of counting AOCI in their regulatory capital ratios. This means their reported capital levels look healthier than the underlying economics would suggest.

Which Banks Carry the Most Risk

The impact of unrealized losses is uneven across the industry. Large banks hold significant dollar amounts of losses but typically hedge their interest-rate exposure with derivatives and maintain more diversified sources of income. They are also required to include AOCI in their capital calculations, so their ratios already reflect some of the pain.

Regional banks are more vulnerable. Many loaded up on long-term securities during the low-rate period and had limited hedging. A subset of these banks still carry unrealized losses that equal half or more of their CET1 capital, which places them in a danger zone from a regulatory standpoint.

Community banks present a different picture. They often hold a high proportion of longer-term assets and benefited from the opt-out that allows them to exclude AOCI from regulatory capital. On paper, their capital looks strong. In reality, their economic equity is lower, and if forced to realize losses they would face significant strain.

How Lending Is Affected

Even if losses remain unrealized, they directly influence a bank’s ability to lend. First, banks treat underwater bonds as essentially frozen, knowing that selling them would damage capital. That ties up resources that could otherwise support new loans. Second, liquidity concerns push banks to hoard cash and safe assets rather than extend new credit.

The outcome is tighter lending standards and weaker credit growth. Commercial real estate lending, particularly for office buildings already struggling with high vacancies, is under significant pressure. Housing and construction loans are also harder to obtain, and small businesses that rely on community banks are facing stricter terms. This reduction in credit supply slows economic activity, acting as a drag on growth even if no crisis erupts.

Deposits and Fragile Confidence

Deposits remain the central risk in this story. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023 demonstrated how quickly uninsured deposits can flee. Since then, deposits have stabilized and even grown in aggregate, but confidence is fragile. A single announcement of losses, a failed capital raise, or a downgrade could trigger renewed outflows at vulnerable banks.

The Federal Reserve’s Bank Term Funding Program, which gave banks the ability to borrow against underwater securities at full face value, expired in March 2024. Without it, banks rely on the Fed’s discount window and Federal Home Loan Bank advances. These facilities still provide liquidity, but at less generous terms, meaning banks cannot count on being fully shielded if depositors bolt.

The Interest Rate Factor

The path of interest rates will determine how this story unfolds. If long-term yields rise again, unrealized losses will balloon, potentially back toward six hundred billion or more. If yields decline meaningfully, the market value of bonds will improve, reducing losses, though mortgage-backed securities recover more slowly due to refinancing dynamics. If rates remain high for an extended period, banks will face a slow grind of weak profits, frozen capital, and gradual consolidation through mergers.

Regulatory Oversight and Market Signals

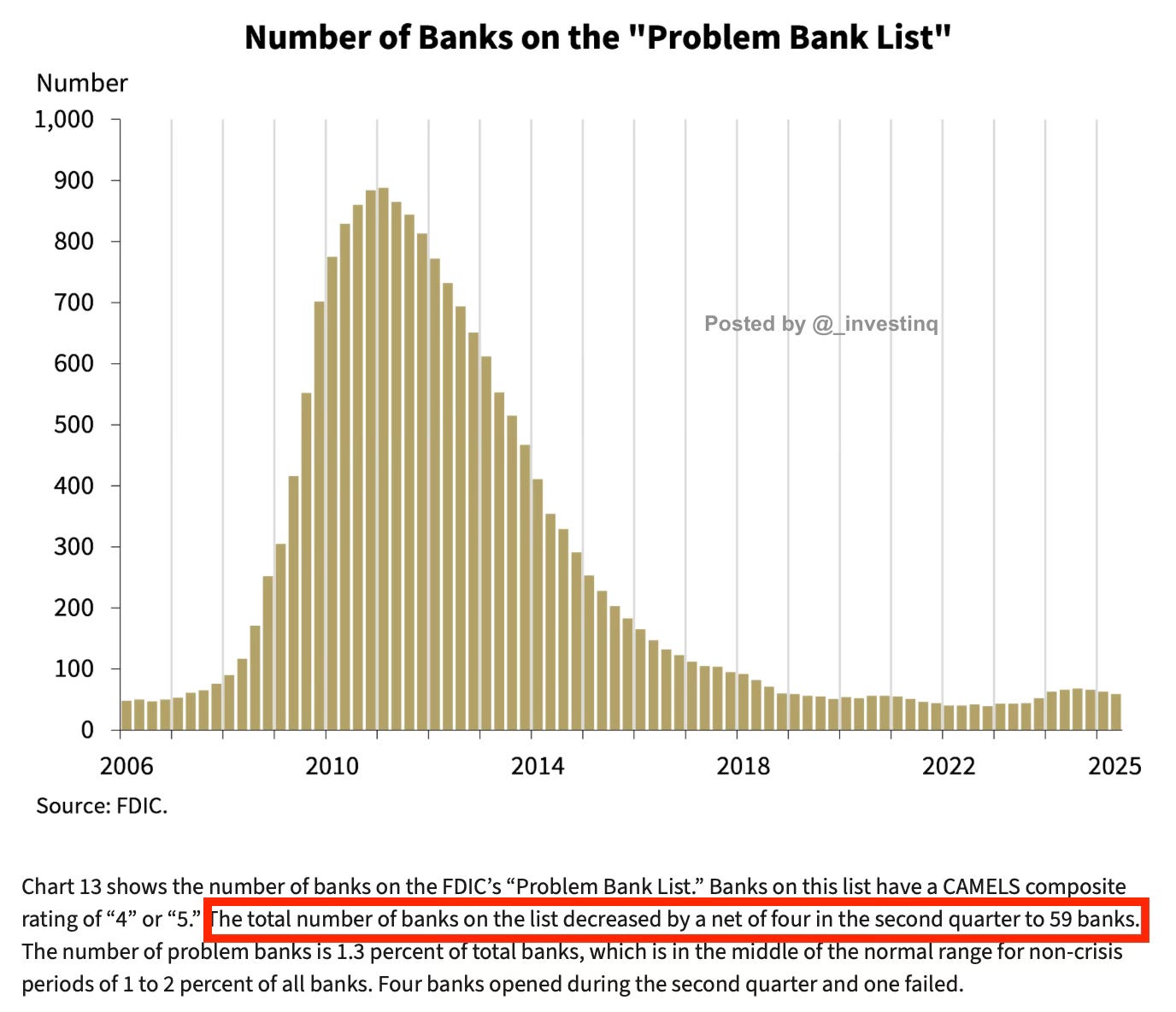

Regulators are closely monitoring these risks. As of the second quarter of 2025, fifty-nine banks were on the FDIC’s Problem Bank List. This is not an alarming number compared to past crises but signals elevated supervisory concern. The Deposit Insurance Fund, which protects insured depositors, held about one hundred forty-five billion dollars, a healthy cushion for isolated failures but insufficient for a systemic wave.

Investors have already priced much of this into the market. Bank stocks, especially regional names, trade at steep discounts to book value. Credit rating agencies cite interest-rate risk and hidden losses when issuing downgrades. Bond spreads remain wider than they were before 2022, raising banks’ funding costs and reinforcing the perception of fragility.

Historical Lessons

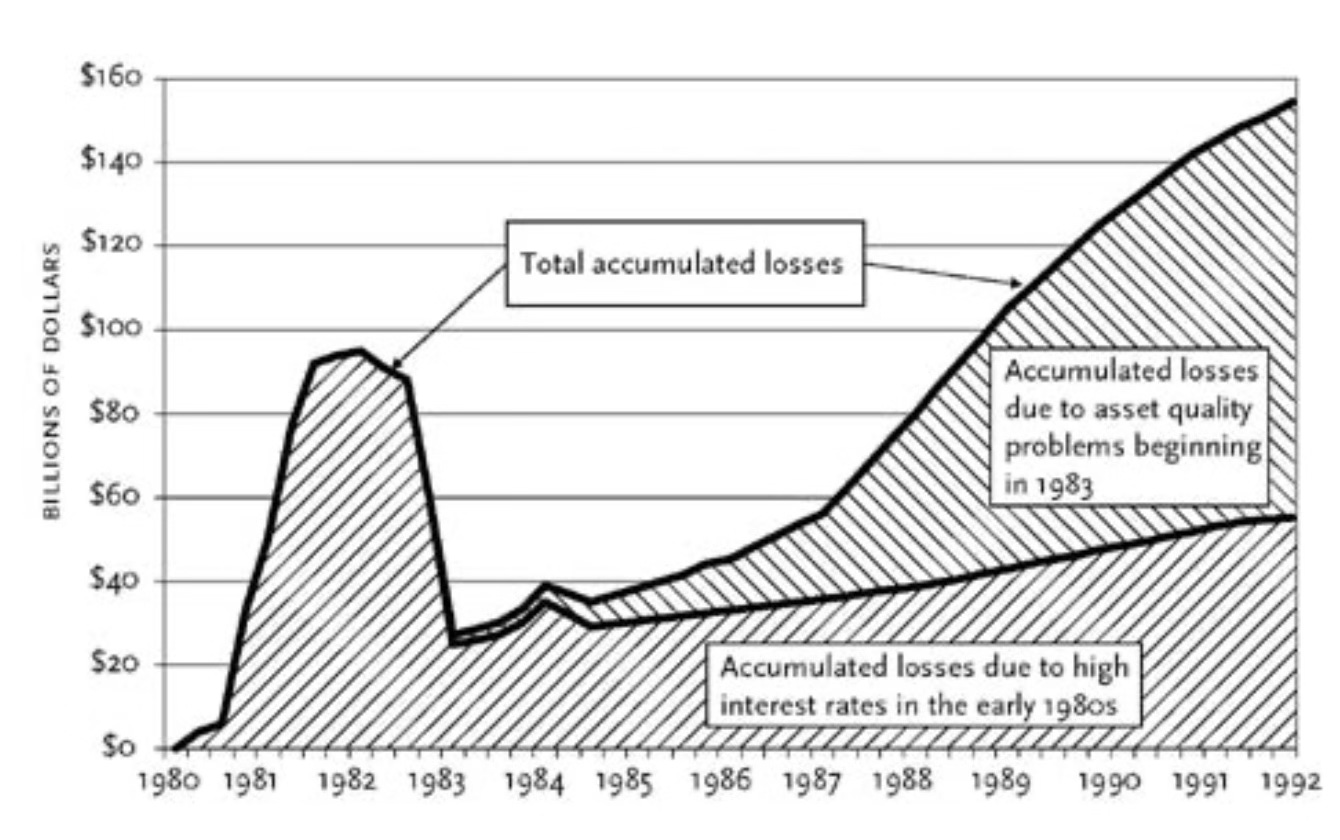

The Savings and Loan crisis of the 1980s provides the clearest parallel. Thrifts at the time held long-term mortgages at low rates that collapsed in value when the Federal Reserve hiked aggressively. Regulators allowed institutions to carry those assets at book value, masking insolvency. Many thrifts later took risky bets to try to grow out of their problems, which led to massive failures and taxpayer-funded bailouts.

The 2008 financial crisis was different in nature driven by credit losses rather than interest-rate risk but similar in its dynamic of confidence unraveling quickly. Once investors and depositors doubted an institution’s ability to absorb losses, liquidity evaporated and even healthy banks came under pressure. The core lesson is that ignoring economic reality, whether it is toxic credit or massive unrealized bond losses, makes the system reliant on fragile confidence.

Conclusion

Unrealized losses on securities remain a defining risk for U.S. banks in 2025. These are not bad loans or speculative bets, but safe assets whose values plunged when rates rose. That makes the problem less about ultimate repayment and more about timing, confidence, and liquidity.

If rates rise further, losses will grow. If rates fall, banks will see relief, though not a complete solution. If rates stay high, the problem will linger, weighing on profitability and lending capacity for years.

The U.S. banking system is more resilient today than it was in 2008, with stronger capital and stricter oversight. Yet the lesson of recent years remains clear: paper losses can quickly become very real if confidence breaks. The challenge is not just about waiting for bonds to mature, but about ensuring that banks, regulators, and markets can navigate the fragile period in between.

Please get Venmo 😂 or, if you have Venmo already, DM me with the info and I will use that method to tip you.